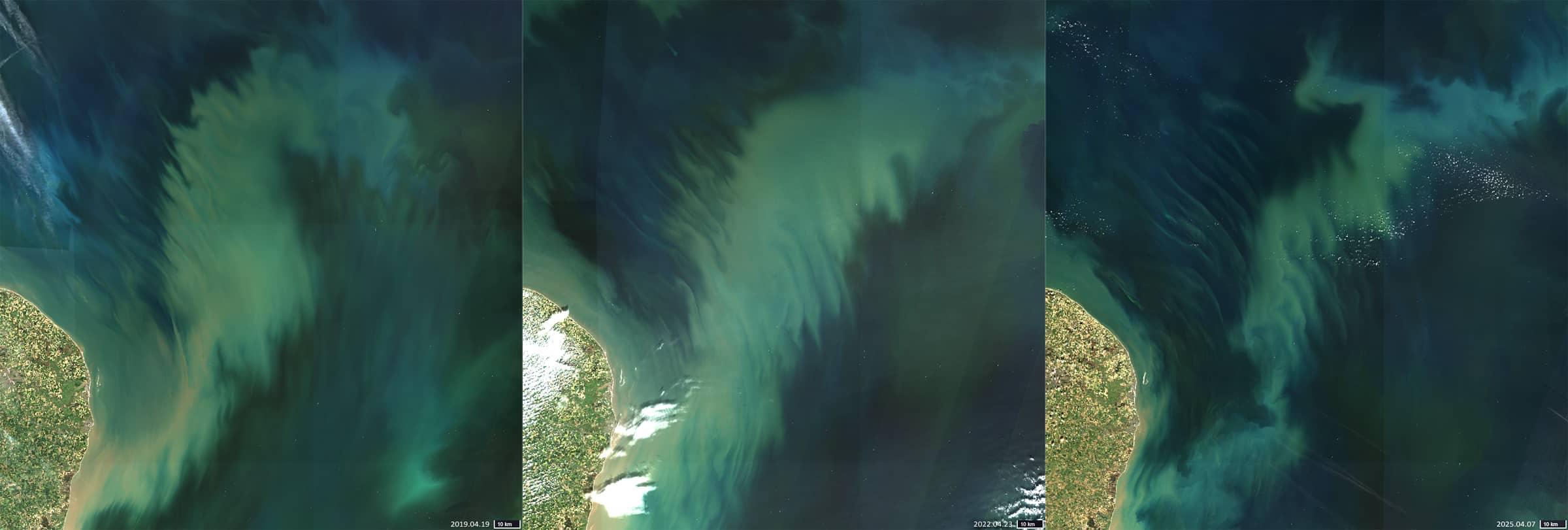

Sediment from the Thames & Wash Estuaries

Between East of England and The Netherlands | North Sea

Dates of acquisition:

• 2025.04.07 | 10:56:41 UTC

• 2022.04.23 | 10:56:21 UTC

• 2019.04.19 | 10:56:21 UTC

Sensor: Sentinel-2A, C L2A

Coordinates: ca. 53°N, 3°E

The composition of the sediments in the Thames and Wash estuaries, and the surrounding southern North Sea reflects the complex interplay of fluvial, tidal, and marine processes.

In the Thames Estuary, sediments are primarily silt and clay, with localised fine to medium sand. These materials originate from river inputs, coastal erosion and marine resuspension. Historically, industrial and urban activities along the Thames have introduced anthropogenic particles, further influencing the sediment characteristics. The strong tidal regime favours continuous mixing, resulting in suspended sediment plumes that are often visible as brown to greyish hueson satellite images, especially at low tide.

The Wash Estuary is characterized by its extensive intertidal mudflats and salt marshes. The sediments hereconsist of well-sorted fine sands, silts, and clays. Much of this material is derived from rivers such as the Great Ouse and the Nene. Due to its relatively lower energy environment compared to the Thames, finer sediments settle more easily here. Organically enriched mud contributes to darker colour tones on satellite images, especially at low tide or in calm conditions.

The Outer Wash and Brown Ridge region of the North Sea, adjacent to these estuaries, has a slightly different sedimentary profile. Shaped by past glacial activity and present-day ocean dynamics, this area contains a mixture of fine sands and silts with a notable presence of finely dispersed limestone particles. These carbonate materials originate from the glacial reworking and erosion of offshore of calcareous layers. On satellite images, the water above Brown Ridge often appears milky or slightly turquoise, due to the reflective properties ofthe suspended carbonate particles.

For example, Figure 1 shows an image from the Sentinel-2 satellite (), which clearly shows the features described in this article.

The colour and turbidity observed in satellite imagery often correlate with algal blooms, which thrive in nutrient-rich, well-mixed waters. A high sediment load can both suppress and stimulate algal growth: fine suspended particles reduce light penetration and inhibit photosynthesis; however, sediments also carry essential nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus. Phytoplankton blooms often occur on the East Anglian coast and near the Wash in spring and summer, when stratification and sola radiation increase, appearing as greenish swirls or streaks on satellite images. The presence of limestone may slightly increase algal productivity by buffering pH and providing trace elements.

Overall, sediment composition influences not only the geomorphology of estuaries, but also plays a key role in biogeochemical cycles that directly affect coastal water quality and ecosystem productivity.

In the southern North Sea region, sediments appear in the same locations on satellite images over time (Figure 2) due to the following reasons:

- The tides, currents, and wave action in estuaries such as the Thames and the Wash tend to follow predictable patterns. These forces cause continuous resuspension and redistribution of sediments within relatively fixed areas, so that plumes of suspended sediment occur repeatedly in the same places. Tidal mixing zones and convergence zones, where currents meet and slow down, are hotspots for sediment accumulation and redistribution, for example.

- The bathymetry (the underwater topography of an area) also contributes to sediment deposition in cetain areas. Shallow banks, channels and mudflats can act as sediment traps or mixing zones. Large intertidal zones allow fine sediments to be deposited repeatedly in the same places, showing up as darker or more turbid regions on satellite images.

Coastal erosion and coastal drift also deposit sediment at predictable spots. They help maintain a relatively steady supply of material that gets suspended and deposited again and again in the same regions.

These suspended particles reflect light, particularly in the visible and near-infrared spectrum, causing bright or milky patches to appear consistently where sediment is constantly stirred up.